Educator Tools

Ask yourself:

Ask yourself:

- How were the events of the Bosnian War portrayed on television and other media? What are the advantages and liabilities of such a media-influenced war?

- Who was behind these media stories and what messages were they trying to convey?

- How did such portrayals affect people’s perceptions of war during that time and how does it affect our own understandings now?

This chapter uses the theme of media as an entry point for discussing and understanding the complexities of the Bosnian War. You will first refresh and practice your media literacy skills by examining and determining the accuracy and reliability of two modern advertisements. You will then analyze an array of primary sources from the war to observe what different journalists chose to publicize or omit from their coverage and how viewers responded to these choices. Ultimately you will be asked to decide whether or not you think the media functioned as an instrument of truth or a device for deception during the Bosnian War.

Welcome to Sarajevo poster on wall with bullet holes and graffiti in Bosnian

Credit: Zlatko Vikovic. WordPress.com

Definitions

Definitions

Media: Means of mass communication that provides information to the public.

Bosniaks: People who identify themselves as descendants of their Bosnian ancestors who embraced the Ottoman Empire and the Islamic religion that it introduced into the region. Because this identification is rooted more in history than religion, these descendants commonly call themselves Bosniaks instead of Bosnian Muslims.

Urbanicide: The deliberate destruction of cityscapes during times of war. This tactic is used to destroy historical and cultural elements of a city and to displace the urban population living there.

Dayton Agreement: An international peace agreement led by the United States in Ohio and signed by the presidents of Croatia, Bosnia, and Serbia (the latter representing Bosnian Serb interests) in November 1995 to end the war in Bosnia. The agreement officially partitioned Bosnia into the Republic of Serbia and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (a shared Bosnian and Croatian territory).

Ustasha (Ustaše): The Croatian fascist movement, aligned with Nazi Germany, that nominally ruled the Independent State of Croatia during World War II. To make their state purely Croatian, the Ustasha exterminated the Serb, Jewish, and Roma minorities in Croatia.

Chetniks: A Serbian nationalist guerrilla force that fought against the Axis invasion, Ustasha, and communists in Yugoslavia.

Ethnic Cleansing: Intentionally and systemically removing members of an ethnic group through intimidation and/or armed force in order to produce an ethnically homogenous territory.

Source: Eric Black, Bosnia: A Fractured Region. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications, 1999.

The war-torn Sarajevo neighborhood of Grbavica in 1996, the site of rape camps during the Bosnian War and the subject of the award-winning film Grbavica

Credit: Wikimedia.com

This really happened

Appearing in various streets in Bosnia’s capital, Sarajevo, in 1992, were posters reminding its viewers of the city’s once brighter past. Less than a decade before, Sarajevo hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics and showcased the peace and prosperity Yugoslavia was enjoying since its former communist leader, Josip Broz Tito, came to power in 1945. Depicted in the poster is Olympic mascot, Vučko the Wolf, sporting an Olympic scarf and crossing his fingers with high hopes for Yugoslavia in the games.

Much of Yugoslavia’s Golden Age (1981-1986) was attributed to the prior work of Tito, who for 35 years helped the country triumph despite a history plagued by ethnic rivalry. He did this by suppressing all forms of ethnic nationalism within the country’s six republics (see Figure 1.2 below) and by promoting “brotherhood and unity” throughout Yugoslavia. Tito’s vision of a united Yugoslavia was most visible in Bosnia, the country’s most ethnically diverse republic, where an increasing number of people married inter-ethnically, spoke the common Serbo-Croatian language, used a combination of Cyrillic and Latin script, and began to identify themselves as Bosnian.

With Tito’s death and the eventual collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, ethno-nationalism resurfaced. By 1989, the Serbian government asserted power over its originally autonomous (self-governed) provinces (Kosovo and Vojvodina) and the republic of Montenegro. In 1991, Slovenia and Croatia declared independence, followed by Bosnia a year later, but these changes did not come without a cost. A series of wars between Yugoslavia’s different ethnicities ensued, culminating in Bosnia.

Unlike its more nationalistic neighbours, the Bosnian coalition government vowed to remain strongly committed to its diverse ethnic population while independent. At the time, Bosnia’s population was 44% Bosniak (Muslims), 31% Serb, 17% Croat, and 8% Jewish, Albanian, and Roma. However, the government’s commitment proved to be unsuccessful as the war severed many of the republic’s ethnic bonds and Bosnia was eventually officially partitioned by ethnicity with the signing of the Dayton Agreement in 1995. During the war, the Serbian government largely backed the Bosnian Serbs to unite all Serbs in an autonomous region in Bosnia, while the Croatian government wavered between doing the same for its people or supporting Bosniak efforts to protect a multi-ethnic Bosnia.

With this in mind, the poster mentioned above not only tells a story of Yugoslavia’s past, but also one of the Bosnian War, where the bullet holes in the poster’s background not only mark the mass destruction caused by urbanicide and genocide, but the deep pain many Bosnian people experienced during this time. The media expressed stories of horror, hate, and honour in the words and images presented by journalists in newspapers, magazines, radio and television broadcasts worldwide. The invention of portable camcorders and satellites enabled not only government officials and journalists, but civilians alike, to instantly report and record their stories of events in real-time. This made the Yugoslavian War the most recorded and first truly televised war in history. But who was behind these stories and what message were they trying to convey? How were the events of the war portrayed on television and other media? And how did this portrayal affect people’s perceptions of the war and our own understanding now?

Establishment of the ICTY and the Question of Responsibility

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) is a United Nations court of law dealing with war crimes that took place during the conflicts in the Balkans in the 1990s. Since its establishment in 1993, it has transformed the landscape of international humanitarian law and provided victims with the opportunity to voice the horrors they witnessed and experienced.

In its precedent-setting decisions on genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, the Tribunal has shown that an individual’s senior position can no longer protect them from prosecution. It has now shown that those suspected of bearing the greatest responsibility for atrocities committed can be called to account, as well as that guilt should be individualized, protecting entire communities from being labeled as “collectively responsible.”

Key Political Leaders

Slobodan Milošević: President of Serbia from 1989 to 1997 who vowed to protect and unite Serbs in Yugoslavia. Milošević faced 66 counts of crimes against humanity, genocide, and war crimes committed during the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s. He pleaded not guilty to all the charges. Due to his death by heart attack during the trial (March 11, 2006), the court returned no verdict on the charges.

Radovan Karadžić: Opposition leader in Bosnia who declared portions of Bosnia to be the Republic of Serbia and served as president of these regions from 1992-1996. He was charged with 5 counts of crimes against humanity and 6 other breaches of international law. A fugitive for over 10 years, he was found guilty of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 40 years imprisonment on March 24, 2016.

Franjo Tuđman (Tudjman): President of Croatia from 1990 to 1999 who led the republic to independence from Yugoslavia in 1991.

Alija Izetbegović: Served as President of Bosnia from 1990-1996 forming a coalition government that included representatives for Bosnia’s Croatian and Serbian populations. Izetbegović represented the Bosniak population, but was committed to upholding a multi-ethnic Bosnia.

Historical Thinking Concepts

Before we begin to explore the role of media in the Bosnian War, we should first recall three of Peter Seixas’s Six Historical Thinking Concepts and understand their relevance for our learning.

Historical Perspectives: Explore the various historical perspectives expressed through multiple forms of media during the Bosnian War. These perspectives and primary sources can then be used as entry points to understand how various social, political, and cultural contexts influenced people’s use of and reaction to media during the Bosnian War.

Continuity & Change: By comparing media at different points during the war, you may be able to detect patterns of continuity and change in how the war was being portrayed in the media. How consistent were the different governments, journalists, and graphic designers in their portrayal of the war? Did anyone’s expression of the war change over time? And, what were the reasons behind the change or lack of change?

Historical Significance: Observe what people choose to publicize or omit from the media as well as the motivations behind these decisions. Assess the extent of accuracy and truth within your media selections.

Artifacts

Artifacts

Artifact One: › Yugoslavian Federal Laws Related to Media under Josip Tito

A. From the Federal Criminal Code of Yugoslavia:

Article 134: “Whoever by propaganda or in any manner incites or fosters national, racial, or religious hatred or antagonism shall be sentenced to one to ten years of imprisonment.”

B. Law on Prevention of the Abuse of Freedom of the Press:

Article 4: “Publishers will provide the local Prosecutor’s office with two copies of every publication before it is released to the public.”

Article 19: “Extended the Prosecutor’s banning powers to radio, television, and other media.”

Source: Thompson, Mark. Forging War: The Media in Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Hercegovina. Bedfordshire, UK: University of Luton Press, 1999.

Artifact Two: › Words Displayed in the Media Prior to the Outbreak of the Bosnian War

“At home and abroad, Serbia’s enemies are massing against us. We say to them: ‘We are not afraid. We enter every battle to win.’ ”-Slobodan Milošević, soon to be President of Serbia, November 19, 1988.

“On this day Christ triumphant came to Jerusalem. He was greeted as a Messiah. Today, our capital is the New Jerusalem. Franjo Tuđman has come to his people!”-Member of the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) after Tuđman became President of Croatia, May 30, 1990.

“We will view any attempt to repress (independent) Croatia as an enemy occupation.” -Stipe Mesić, Croatian Prime Minister, 1991.

“Bosnia won’t stay in a Yugoslavia run by Serbia. I won’t let Bosnia be part of Greater Serbia.” -Alija Izetbegović, President of Bosnia, 1990.

“I warn you, you’ll drag Bosnia to hell. You Muslims aren’t ready for war—you could face extinction.” -Radovan Karadžić, leader of the Serb Democratic Party (SDS) in Bosnia, 1990.

Source: BBC. The Death of Yugoslavia (Documentary). 1995.

Artifact Three: › The Use of and Reaction to Media during the Bosnian War, 1992-1995

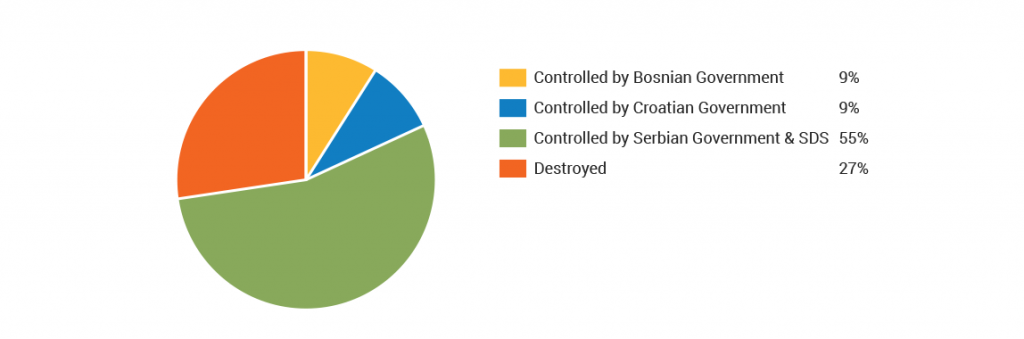

A. Status of Main Television Transmitters in Bosnia by 1993

Source : Forging War, 1999

B. Three Reports on the Situation in Kupres, South Western Bosnia (April 1992)*

An independent newspaper in Croatia, Slobodna Dalmacija, “reported when Kupres fell to Serb forces on 9 April,” while the Federal Croatian television station, HTV, did not. The same evening, “viewers of Serbia’s TVB news learned from a reporter that, “After fifty years, Kupres is free! For a further three days . . . HTV reported that ‘Kupres is securely in Croat hands.’ Consequently, Slobodna Dalmacija received angry phone calls, accusing it of defeatism. Refugees from the Kupres area later [said] they had believed the HTV reports and were almost caught in the Serb advance.”

*This type of reporting on events was typical during the Bosnian War.

Source: Forging War, 1999.

C. Reporting on Concentration Camps used for Ethnic Cleansing during the Bosnian War

“Foreign journalists arrived and began to film us. They caught me first, next to the barbed wire, and I began to talk when one of the guards standing behind said: ‘Record the names of all those talking so we can kill them.’ I hardly said anything, except I was hungry and exhausted . . . Everyone who said more to the journalists and had their names recorded was (sic) taken by the Serbs that night—to be killed.”

– Bosniak male, who also claimed the same news story saved his life and the lives of many others.

Serb-run concentration camps, including Omarska and Manjaca, were the first found and mediatized, but Bosniak and Croatian special military forces also constructed their own camps for similar purposes.

Source: Weine, Stevan M., History Nightmare. London: Rutgers University Press, 1999.

D. Language in the Media*

“In autumn 1993, the Chief of Staff of the ABiH** , General Rasim Delić, issued an order to the Sarajevo media to call the HVO by the title not (Ustasha forces) and to call the Serb forces ‘paramilitary units of Bosnian Serbs’ or ‘Yugoslav Army’ (not Chetniks). The order did not work for long, even in RTVBiH***.”

“According to New York Times reporter John Burns, (a) young soldier, had ‘absorbed and accepted a view of Muslims which contradicted his own experience of growing up in a nationally mixed part of Sarajevo. From Serbian radio, television, and in gatherings with other Serbian fighters . . . he learnt Muslims posed a threat to Serbs . . . were planning to declare ‘an Islamic republic’ in Bosnia (and) would require children to wear Muslim clothing.”

*Language was similar in Croatia. Some forms of media being more nationalist than others.

** Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina

***Federal Bosnian television station

Source: Forging War, 1999.

E. A Change in Serbian Media (1994-)

“The War in Bosnia continues, but for our television screen it no longer exists,” said a Serbian TV correspondent. A Politka editor declared: “We are trying to control passions in Serbia.”

Milošević began to distance himself from Radovan’s mission of uniting all Serbs in Bosnia and instead directed his focus to peace negotiations, in which he later represented the interests of Bosnian Serbs.

Source : Forging War, 1999

ACTION 1

Discuss

The powerful influence of the media

Take a close look at the artifacts provided above and discuss the following questions with a partner:

- To what extent do you think the media influenced the beliefs and actions of its viewers? Imagine reading these stories as they were happening in your own country.

- What are some of the benefits, drawbacks, and dangers of such a mediatized war?

- In the 1990s, Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia had media laws that were similar to Tito’s, but why then did history unravel differently after Tito’s death? Do you think media should be censored?

- What implications do you think Serbia’s change in media had? Was the change for better or for worse? And for whom? Please explain your reasoning.

- After studying the artifacts provided, do you think media acted as an instrument of truth or a device for deception during the Bosnian War? Why? Justify your reasoning using at least 3 artifacts.

- How does media from the Bosnian War influence our current understanding of the period? Are there any overarching themes/common messages that arose? Are you left with any unanswered questions?

ACTION 2

Think

Read the following statement made in the International Commission Report on the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913.

“The real culprits in this long list of executions, assassinations, drownings, burnings, massacres, and atrocities by our report, are not, we repeat, the Balkan peoples . . . The true culprits are those who mislead public opinion and take advantage of people’s ignorance to raise disquieting rumours and sound the alarm bell, inciting their country and consequently other countries into enmity.”

Source: Forging War, 1999.

Reflections:

- How does this statement apply to what we have learned about the role of media in the Bosnian War?

- To what extent do you agree or disagree with this statement, and why?

ACTION 3

iSearch

Further Reflection:

Explore the following websites on the ICTY while considering the actions of the global community and our responsibility for humanity.

UN International Criminal Tribunal – Central Bosnia

Trial International – Bosnian War Crimes

And this one:

War Crime Tribunal

Think

Reflections:

- What is the responsibility of the global community of nations in response to ethnic strife given the developing precedents of International Law going back to Nuremberg?

- How are we as global citizens implicated in ongoing ethnic conflicts around the world when we fail to act to protect the vulnerable citizens caught in these horrific events?

ACTION 4

Discerning Truth from Fiction in Media Today

As we know, virtually anyone can publish their ideas on the Internet. While this can be empowering, it can also pose a threat to facts about issues and events that have happened or are currently occurring. News comes at us in so many forms, and unfortunately, so much of it is biased and worse – completely untrue. As media consumers, we’re being targeted by various agencies and companies aiming to get our attention.

When we click on an image or a product, it increases a site’s traffic and earns revenue from advertisers and potential investors. We are so quick to click when what’s popping up on our social media feed aligns with our interests and beliefs. This is a problem. We’re being targeted within our feeds – our “echo chamber” (an enclosed space for producing reverberation of sound) and thus, we are only taking in our own beliefs reflected back to us. We’re missing the whole truth.

What about the other side? An alternate perspective? It is damaging to the truth to merely hear what we want to hear, rather than all sides of a particular story. When we don’t question what we’re reading online, we’re not engaging in critical thinking and are potentially endangering our democracy and freedoms. After all, multiple perspectives lead to a more well-rounded, knowledgeable view of our world.

It would benefit all of us, regardless of age, to learn how to determine what is factual by conducting responsible research using credible sources. In this ever-changing media landscape, you need to learn how to find factual information and what to look for in sources when researching different subjects. Becoming more savvy, digital citizens means learning about media bias, online “fake news,” and the difference between fact and opinion.

Do

You will choose or be assigned a current event and asked to record three facts about the subject. Prior to presenting your facts, please do the following:

- Learn to spot fake news: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g2AdkNH-kWA

- Check the URL to ensure that the site is credible. Here are some filters to run your news item through to check its credibility: https://www.aarp.org/money/scams-fraud/info-2017/fake-news-alert-fd.html

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming

Educator Tools