|

Unit 1: Human Rights

Chapter 3: The Black Experience

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Educator Tools

|

| Dates | Events in History |

|---|---|

| 1603 | The first known Black man to arrive in Canada was Mathieu DaCosta. He acted as a translator between the Mi’kmaq and the French with Champlain. Clearly, DaCosta had been in Canada some time previous to Champlain’s voyage of discovery, since Mi’kmawi’simk (the Mi’kmaq language) is not a European or an African language. |

| 1628 | The first known slave in Canada, Olivier LeJeune, was a child of 6, who was captured in Africa and was later given the surname of one of his owners—a priest. |

| 1775 | During the American Revolution the British forces were led by Lord Dunsmore. In an effort to weaken the “rebel” side, Dunsmore invited all rebel-owned African male slaves to join the British side. |

| 1779 | With the hopes of winning the American Revolution, the British under Sir Henry Clinton, invited all Black men, women, and children to join the British side and promised them their freedom for doing so. Ten per cent of the Loyalists coming into the Maritimes are Black. |

| 1793 | The Upper Canada Abolition Act, supported by Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe, freed any slave who came into the (now) province of Ontario, and stipulated that any child born of a slave mother should be free at the age of 25. |

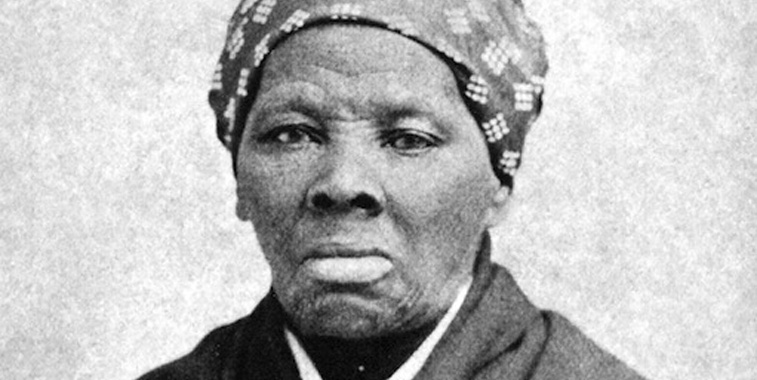

| 1800 – 1865 | Approximately 20,000 Blacks found their way into Canada via the Underground Railroad. Harriet Tubman, one of the most famous “conductors” on the Underground Railroad, spirited several hundred fugitive slaves into Canada, despite a $40,000 reward for her capture, dead or alive. |

| 1812 | The Cochrane Proclamation invited refugees of the War of 1812 to become British citizens through residence in British territory, including Canada. The settlement of Oro was established by the government for Black veterans of the War of 1812. A Coloured Corps was formed after petitioning by Black veteran Richard Pierpoint. |

| 1833 | The British Imperial Act abolished slavery in the British Empire (which included Canada) effective August 1, 1834. |

| 1850 | The second Fugitive Slave Act was passed in the United States, placing all people of African descent at risk. The Underground Railroad stepped up its operations—freeing enslaved Blacks by transporting them into Canada. The Common Schools Act was passed in Ontario, permitting the development of segregated schools. The last segregated school in Ontario closed in the 1950s. |

| 1853 | Mary Ann Shadd left teaching in the U.S. to join with Samuel Ringgold Ward and her brother Isaac in publishing and editing the Provincial Freeman, one of the two Black newspapers published in Ontario from 1853-1857. Mary Ann Shadd was acknowledged as the first Black newspaperwoman and the first woman publisher of a newspaper in Canada. |

| 1857 | William Hall of Nova Scotia became the first Canadian sailor and the first person of African descent to receive the Victoria Cross for bravery and distinguished service in 1861. Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott became Canada’s first doctor of African descent. |

| 1885 | Delos Roget Davis of Amherstburg, Ontario became one of Ontario’s first Black lawyers. He was appointed King’s Council in 1910. |

| 1894 | William Peyton Hubbard became the first Black council member elected to Toronto City Council, and was re-elected council member for 13 successive elections. He served on the Board of Control, and as acting Mayor on a number of occasions. |

| 1905 | The beginning of the “Black Trek,” the migration of dissatisfied African-Americans from Oklahoma to the Canadian prairies. That year, a group led by W.E.B. DuBois and Monroe Trotter met secretly in Niagara, Ontario, to organize resistance to U.S. racism. |

| 1914 | During the First World War, Black Canadians joined combat units, despite opposition, and in 1916, a segregated unit, the Nova Scotia Number 2 Construction Battalion, was formed. |

| 1939 | In the Second World War, authorities again tried to keep Blacks out of the armed forces, but they insisted on serving their country. Eventually, they joined all services. |

| 1948 | Ruth Bailey and Gwennyth Barton became the first Blacks to graduate from a Canadian School of Nursing. |

| 1950’s | New laws made it illegal to refuse to let people work, to receive service in stores, or restaurants, or to move into a home because of their race. |

| 1951 | The Reverend Addie Aylestock became the first Black woman to be ordained a minister in Canada. The following year, Wilson Brooks, an RCAF veteran, became Toronto’s first Black public school teacher, and in 1959, Stanley Grizzle was the first Black person to run for a seat in the Ontario Legislature. In 1963, Leonard Braithwaite, elected to the Ontario legislature, was the first Black person to serve in a provincial legislature in Canada. |

| 1962 | Daniel G. Hill, an American-born Black activist and writer who moved to Canada in 1950, was made the first director of the Ontario Human Rights Commission, the first government agency in Canada set up to protect citizens from discrimination. Hill later became chair of the commission. |

| 1968 | Canada saw the election of its first Black Member of Parliament – The Honourable Lincoln Alexander, of Hamilton. In 1979, he became Canada’s first Black cabinet minister, as Minister of Labour in the federal government. In 1985, he became Ontario’s first Black Lieutenant Governor, and the first Black person to be appointed to a vice-regal position in Canada. |

| 1969 | The first Black History Week was celebrated. Maurice Alexander Charles became the first Black provincial judge of Ontario. |

| 1978 | The Ontario Black History Society was founded by Dr. Daniel Hill, Wilson Brooks, and Lorraine Hubbard. The society is dedicated to the acknowledgement and preservation of the contributions to Canada’s development by Canadian Blacks. |

| 1991 | Julius Alexander Isaac, a native of Grenada, was named Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Canada. He became the first Black Chief Justice in Canada and the first to serve on the Federal Court. |

| 1993 | Jean Augustine was sworn in as Canada’s first Black female Member of Parliament. |

Source: Government of Ontario Press Releases, January 2002

iSearch

In pairs, choose one of the dates/events from the above list. Find out more about this event by doing some research at the library or on the internet. Present your findings to the rest of the class.

The Formation of African Nova Scotian Communities

Black Loyalists, 1783-1785

The single largest group of people of African descent ever to come to Nova Scotia, arrived in a two-year period at the end of the American Revolution. These were the Black Loyalists. They were Blacks in the American colonies who opted to side with the British during the American Revolution of 1776, largely because the British offered protection, freedom, land, and rations in return for support. Other Black people would come to Nova Scotia in the 1780s as the property of White Loyalists. Some were slaves; others were indentured servants, though there was not much difference between the two categories.

When the war ended in 1783, New York was the last British-held port. It became the embarkation point for thousands of Loyalists, Black and White. British officials drew up a detailed list of all the Blacks who were leaving. That list, the “Book of Negroes,” stated whether the person was free, a slave, or an indentured servant, and their military service.

Between 3,000 and 3,500 Black Loyalists arrived in Nova Scotia. Roughly half – 1,521 men, women, and children— settled at Birchtown (near Shelburne) that became an instant town, and the largest settlement of free Blacks in the world outside of Africa. They received a percentage of the free land and rations as they were promised, though their land was far from the best–that went to the White Loyalists. The other 1,500 or so free Blacks who came to Nova Scotia settled elsewhere, including Annapolis, Digby, Preston, Guysborough, Tracadie, and Saint John (in what became New Brunswick).

Disappointed by the failure of the British to honour all their promises, especially regarding land and equal status, many Black Loyalists began to wonder if Nova Scotia was where they wanted to live. A new destination, across the ocean in Africa, appealed to many of them. In 1792, some Black Loyalists departed Nova Scotia for Sierra Leone, while many stayed and helped to develop the province.

Black Loyalists, 1783-1785

The Jamaica Maroons, 1796-1800

Just as the end of the American Revolution brought the Black Loyalists to Nova Scotia, so the end of the next war brought a different group of Black settlers to the province. The second group came from Trelawney, Jamaica and were known as the Trelawney Maroons after their home town.

The Maroons were a determined group of freedom fighters in Jamaica. Beginning in the 1650s, they waged war against the British administration on the island intermittently for nearly a century and a half. They were denied the independence they wanted because in 1795 the administration in Jamaica decided to remove the Maroons from the island. Consequently, in late June, 1796, the Maroons (543 men, women, and children) were sent to Halifax in three ships.

The Commander-in-Chief for the British in Halifax was Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent (later on, the father of Queen Victoria). Edward was impressed by the proud bearing and military skills of the Maroons. He was pleased to see them join Nova Scotia militia units and he had them work on building projects such as the third Halifax Citadel and Government House (residence of the lieutenant-governor). Lt. Gov. Sir John Wentworth was also impressed by the Maroons. He thought they would be good colonists and selected the Preston area for them to settle. Thanks to a large subsidy from the government of Jamaica, arrangements were made for limited schooling and religious services for the new settlers.

The Maroons, however, rejected the idea of low-paid physical labour. The few who became farmers were Christians who settled in Boydville, in the Sackville area, where there is still a Maroon Hill. Similar to about half the Black Loyalists a few years earlier, most other Maroons who did not farm began to wonder if Nova Scotia was a good choice for their new home.

Although the majority of the Maroons left Nova Scotia, there were a few who remained. A census done in 1817 of the Black community of Tracadie in Guysborough revealed that several persons living there were descendants of the Maroons. The Maroons also left descendants in the Preston Area of Halifax County.

The War of 1812 Refugees, 1812-1816

A third wave of Black migration into Nova Scotia came during and after the War of 1812, once again in connection with an international conflict. As the British had done during the American Revolution, they issued proclamations again to attract Blacks in the United States to relocate to the British Colonies in Nova Scotia. A large number of American Blacks chose the freedom that Nova Scotia offered over slavery in the United States, just like the Black Loyalists who preceded them.

In 1813-1814, approximately 1,200 Black refugees from the Chesapeake Bay area of Virginia and from Georgia arrived in Nova Scotia aboard British ships. Another 800 southern American Blacks came to Nova Scotia at the end of the war via Bermuda. Smaller numbers continued to trickle into the province until 1816.

Though there was a labour shortage in Nova Scotia at the time, the Black refugees were not welcomed by the locals. A number of the refugees were quarantined on Melville Island, near Halifax, and the local House of Assembly petitioned to end Black immigration. Lt. Gov. Sir John Sherbrooke dismissed the petition.

Almost 1,000 refugees ended up in Preston. Other areas settled by War of 1812 refugees were Upper Hammonds Plains, Beech Hill (later Beechville) and Campbell Road (later Africville). Collectively, the newcomers faced discrimination in land grants, jobs, and the distribution of supplies. Their situation was made worse by the “year with no summer” followed by the “year of the mice” – a crop-destroying infestation of rodents. There was also an economic recession at the end of the war.

Ninety-five of the original 1,000 refugees opted to leave Nova Scotia and migrated to Trinidad. The remaining settlers stayed in Nova Scotia, overcoming obstacles of poor land and widespread racism and not only survived, but thrived. Some of their customs, language, and religious practices are an integral part of the African Nova Scotian community to this day.

The War of 1812 Refugees, 1812-1816

Bedford Basin near Halifax (Nova Scotia) by Robert Petley 1835

Source: National Archives of Canada

Caribbean Migrants, 1920

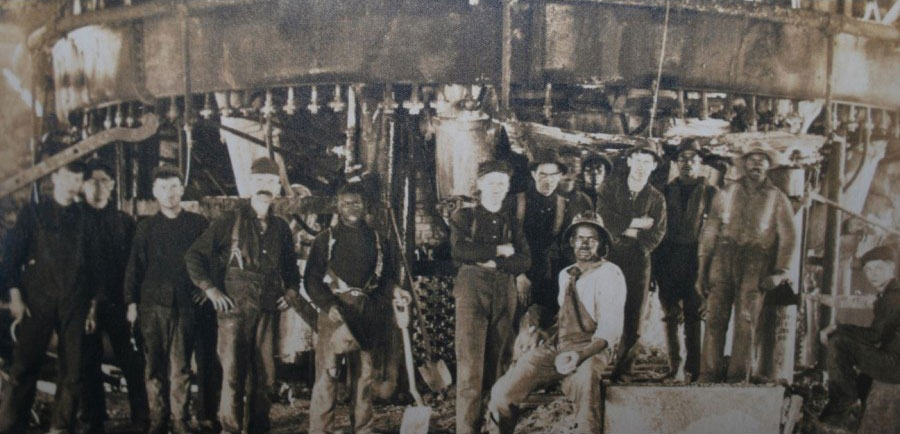

A fourth major migration of Blacks to Nova Scotia – more specifically to industrial Cape Breton – began early in the 20th century. It came in two separate streams, one from Alabama and another from the Caribbean, especially Barbados. These groups came not in a quest for freedom, but to obtain well-paying jobs in the newly developing steel and coal industries.

The group that came from Alabama were specially recruited by the Sydney steel plant to come and work in the “boomtown” economy in connection with the new blast furnace. At the time, Black iron workers in the United States were regarded as among the very best. It is unknown exactly how many men relocated from Alabama in 1901 when the Sydney plant began operations, but there were several hundred. Some were accompanied by women and children. The newcomers settled mostly in the Whitney Pier area of Cape Breton and they saw to it that they had a church and that their children received an education.

Despite the promising beginning, the relocated Alabama community felt less than fully accepted accepted by the locals in Cape Breton. Labour strife, local prejudices, and unfulfilled promises convinced nearly all to return to the United States by 1904. Many walked back though a few stayed on, finding new ways to make a living in the greater Sydney area.

Over the next decade, many small groups of Blacks from the Caribbean found their way to Cape Breton. They sailed north in the hopes of economic advancement and a great number of them ended up working in the coal and steel industries. Whitney Pier was one area they settled and other communities were created. The transplanted Caribbean beliefs and customs added a vibrant, new dimension to Cape Breton life.

Caribbean Migrants, 1920

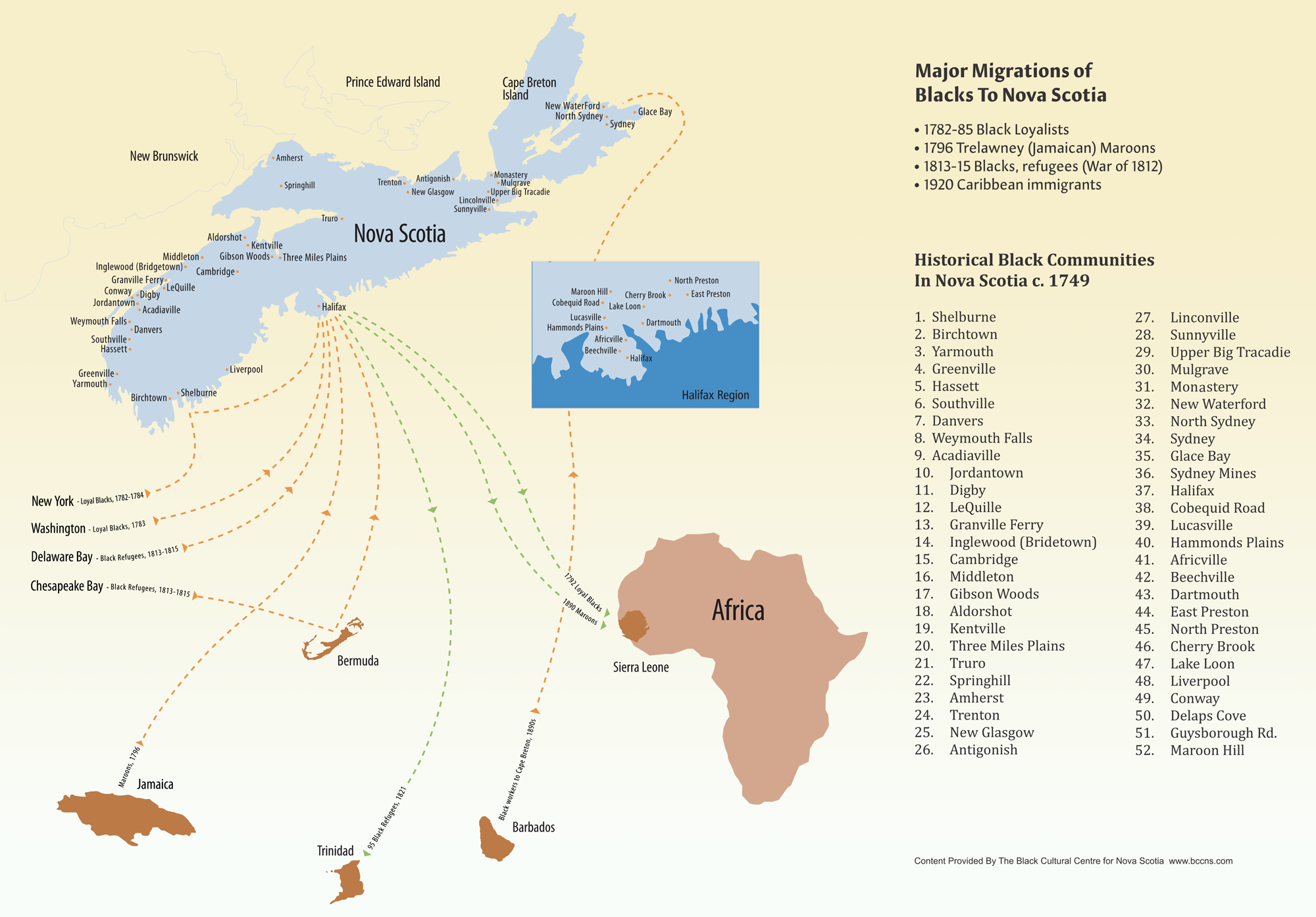

Historical Black Communities and Migration Routes

The historical Black communities of Nova Scotia are unique. This map shows the migration routes and the original Black communities of Nova Scotia.

Nova Scotia, the birthplace of Canada’s Black community, is home to approximately 20,000 residents of African descent. Their presence traces back to the 1600s, and they were recorded as being present in the provincial capital during its founding in 1749. Waves of migrants came to the Maritimes as enslaved labour for the New England Planters in the 1760s, Black Loyalists between 1782 and 1784, Jamaican Maroons who were exiled from their homelands in 1796, Black refugees of the War of 1812, and Caribbean immigrants to Cape Breton in the 1890s. People of African descent continue to put down roots in Nova Scotia, shaping a unique cultural identity that is ever evolving.

Text adapted from Cultural Assets of Nova Scotia: African Nova Scotian Tourism Guide.

Learn more about African Nova Scotian History at www.bccns.com

Source: The Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia

Historical Black Communities and Migration Routes

Righting Wrongs

In 2017, the government of Nova Scotia helped Black Nova Scotians reclaim their land.

In 2022, PM Justin Trudeau apologized to Black WWI soldiers and their families for the racism and discrimination they faced.

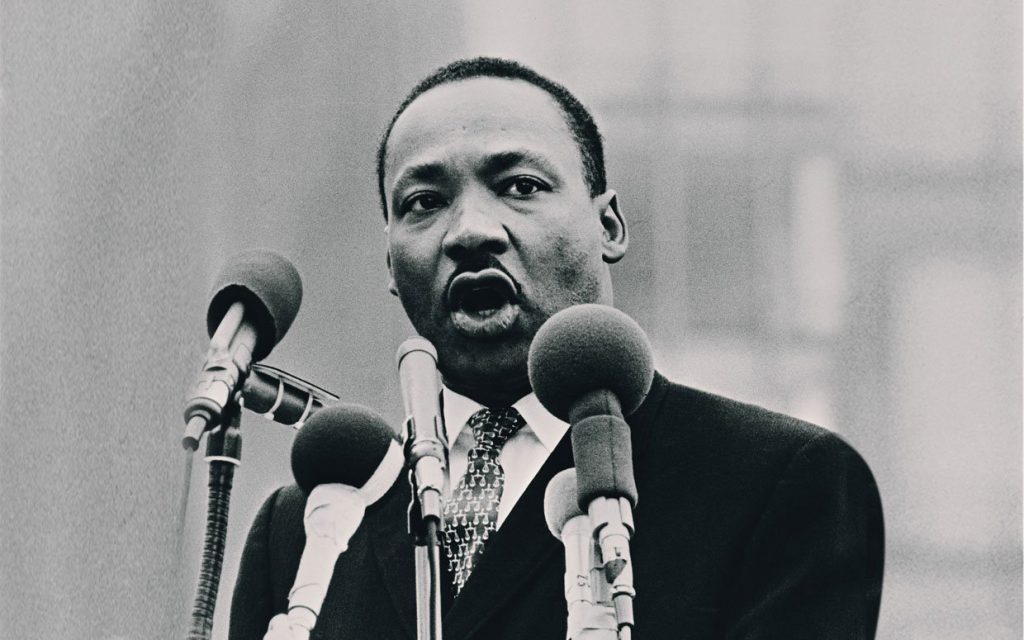

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led the modern American Civil Rights Movement from December 1955 until April 4, 1968. Thanks to his relentless pursuit of equal rights for African Americans, they achieved more genuine progress toward racial equality in America than in the previous 350 years. Dr. King is widely regarded as America’s pre-eminent advocate of non-violence and one of the greatest non-violent leaders in world history. In 1964, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his peaceful resistance to racial prejudice in America.

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day is a federal holiday in the United States. It is observed on the third Monday of January each year, which is around King’s birthday, January 15.

Nelson Mandela and Apartheid South Africa

Definitions

Definitions

Apartheid: government mandated policy of segregation between Whites and non-Whites in the Republic of South Africa from 1948 to 1994. The National Party was dominated by White Afrikaners who enforced legislation to curtail the rights, movement, and associations of the majority Black population. The word comes from Afrikaans and means “the state of being apart.”

The system of apartheid originated in earlier laws but once legislated by the National Party in 1948 it became far more rigid, with segregation being enforced to a much greater degree. At the time it was introduced, the system was justified by racial superiority, as well as the fear of being overwhelmed politically by the majority non-White population. The Dutch Reformed Church of South Africa, established in 1652, commissioned several studies to show justification of apartheid in the Bible and was very supportive of the apartheid system.

Source: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/174603/Dutch-Reformed-Church

Here are the facts

Apartheid Laws

Non-Whites (Black Africans, Indians, Cape Coloureds) had to follow rules or risk arrest. The 1953 Reservation of Separate Amenities Act made it against the law for non-Whites to:

- Enter a restaurant, movie theatre, post office, stadium, and some stores

- Use beaches, park benches, or other places designated “Whites Only”

- Use trains, buses, public toilets, and other transportation designated “Whites Only”

- Receive an education in schools for Whites (a separate, vastly inferior school system was created for non-Whites)

- Enter a hospital or office for Whites unless employed there

- Engage in sexual relations with a person of a different race

- Own land

- Be buried in a cemetery for Whites

- Vote or engage in politics

Timeline of Apartheid

National Party elected, 1948

The all-White government immediately began enforcing existing policies of racial segregation under a system of legislation that it called apartheid.

Population Registration Act, 1950

Non-Whites had to carry identification or “passes” at all times to show police upon request. The Department of Home Affairs had all South Africans register by their racial group and they would be treated accordingly.

Group Areas Act, 1950

Physical segregation of the races mandated that non-Whites were only allowed to live in designated “townships” for non-Whites that were outside the main towns. They had vastly inferior living conditions mostly with no running water, sewage, or electricity. Non-Whites could only rent property since land was White-owned.

The Suppression of Communism Act, 1950 (formerly Unlawful Organizations Act)

All those who opposed or resisted the government were labeled as communist.

Bantu Education Act, 1953

A separate and inferior education system was created with the goal of a curriculum that produced manual laborers and obedience. A huge percentage of the population remained illiterate as adults.

Promotion of Bantu Self-Government, 1959

Black people were moved into homelands created in the worst parts of the country on infertile land. People lost their homes and had to move off land they owned for years to these undeveloped areas far from cities where they had jobs.

Publication Act, 1978

The government took control of the media through state censorship.

Police Act, 1979

Granted the police further powers with regards to search and seizure.

1993

Apartheid was dismantled following negotiations from 1990 to 1993.

Government Censorship

In order to promote apartheid and essentially segregate South Africa from the rest of the world, there was rigid censorship of movies, books, magazines, radio, and television programs. Television was only introduced nationwide in the country in 1976 and was heavily controlled to avoid exposure of the lives of Black people in other countries. (By comparison, television was officially introduced into Canada in 1952.) The new medium was then regarded as the “devil’s own box, for disseminating communism and immorality.”

Even for Whites there was no freedom of speech or freedom of press and any opposition to the government was not tolerated. Breaking any of the apartheid rules was considered a form of protest and a communist act (for example, a White person going to a “non-Whites only” designated area). Meetings of groups were monitored. A police tate was in effect for all South Africans. There was no such thing as a fair trial for non-Whites or for Whites who resisted.

Source: Apartheid and Reactions To It

Timeline of Apartheid Opposition

| Dates | Events in History |

|---|---|

| 1948-49 | The African National Congress (ANC) began as a non-violent organization of African workers unions to encourage mass action through civil disobedience, strikes, boycotts, and other non-violent forms of resistance. |

| 1952 | Nelson Mandela led The Defiance Campaign, the first large-scale multi-racial political campaign against apartheid laws, involving all groups of non-Whites. Eight thousand trained volunteers were jailed for “defying unjust laws” such as failing to carry passes, violating curfew hours, and entering “Whites only” public places. The government could incarcerate protesters for up to five years, and fine them heavily. |

| 1956 | An Anti Pass Campaign, after the government extended the pass law to women, led to a mass demonstration of 20,000 women of all races at government buildings in Pretoria, the capital. |

| 1956 | With the goal of increasing opposition, the ANC adopted the Freedom Charter. It resulted in the arrest and charge with treason of 156 of its leaders (104 Africans, 23 Whites, 21 Indians and 8 Coloured). Nelson Mandela was one of those arrested (but in 1961 was found not guilty). |

| March 21, 1960 | The Sharpeville Massacre: in the township of Sharpeville, the PAC (Pan Africanist Congress) organized a peaceful protest against the pass laws. It became a brutal massacre when heavily armed police opened fire, killing 69 and wounding over 200 protestors. On March 30th, the government declared a state of emergency. |

| 1962 | The Special Committee Against Apartheid, established by the United Nations, inspired international pressure against apartheid in the form of sanctions and media campaigns. |

| 1968 | Medical student Steve Biko co-founded the South African Students Organization (SASO) based on the philosophy of black consciousness, encouraging blacks to embrace their cultural identity and reject all notions of inferiority and foreign status in their own land. |

| 1974 | South Africa was expelled from the United Nations. |

| June 16, 1976 | The Soweto Uprising (also called 16 June): after the government mandated the use of Afrikaans as the language of instruction in schools, about 15,000 to 20,000 high school students began a series of protests. During a peaceful march, police opened fire and killed 600 high school students. |

| 1977 | International pressure was building as the UN Security Council voted to place a mandatory embargo on the sale of arms to South Africa. |

| August 18, 1977 | Death of Steve Biko: Steve Biko, leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, was beaten to death while in custody. Mandela said, “They had to kill him to prolong the life of apartheid.” (The five police who killed him were never prosecuted and in 2003 the justice ministry claimed too much time had passed and there was insufficient evidence for prosecution.) |

| 1980 | The UN Security Council officially condemned police violence in South Africa, and called for the end of apartheid, the granting of equal rights to all citizens, and the release of political prisoners. |

| 1980s | Tricameral Parliament established: Prime Minister P. W. Botha attempted to appease citizens, in response to significant internal pressure. He formed a group that included colored (mixed-race) and Indian legislatures, but still excluded Black Africans. As the white legislature maintained all political power, this attempt was purely for show. |

| 1983 | The United Democratic Front (UDF) was formed to oppose the Tricameral legislature and grew to over 3 million members. It adopted the ANC’s Freedom Charter, (linking itself to the still-banned organization) with Archbishop Desmond Tutu as one of its most prominent members. |

| 1986 | South Africa’s economy was drastically affected when the United States and the United Kingdom placed economic sanctions on the country. In response, the government began to ease its enforcement of smaller rules of apartheid, by rolling back the pass laws’ restrictions on Black access to public space. |

| 1989 |

F. W. de Klerk was elected president. He eliminated most of the legal basis for apartheid and lifted the ban on the ANC freeing many political prisoners. |

| 1990 | Nelson Mandela was released from prison after 27 years on Robben Island. Quebec MP Irwin Cotler went to South Africa to serve as his legal counsel. |

| 1991 |

The Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) began negotiations to form a multiracial transitional government with a new constitution offering political rights to all groups in an “undivided South Africa.” |

| June 17, 1992 | Boipatong massacre: 200 IFP militants attacked the Gauteng township of Boipatong, killing 45. |

| September 7, 1992 | The Bisho massacre: ANC protestors demanded that the Ciskei Homeland be reincorporated into South Africa. The Ciskei Defence Force opened fire on them killing 29 people and injuring 200. Afterward, Mandela and de Klerk agreed to meet to find ways to end the spiraling violence. |

| 1993 |

Parliament approved an interim constitution granting Black majority rule for the very first time since South Africa was colonized. |

| 1994 | After three centuries of white domination in South Africa, Nelson Mandela became the first president in the country’s first democratic election. |

| 1995 | Desmond Tutu led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to gather data on human rights’ violations of apartheid. |

| 1996 | After the first non-racial elections of 1994, the South African Parliament drew up the Constitution and Bill of Rights based largely on Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms and promoted by President Mandela (officially coming into effect on February 4, 1997) |

| 1998 | The TRC branded apartheid as a crime against humanity and requested financial, symbolic, and community reparations to its victims. |

Nelson Mandela (Madiba) – Biography

Nelson Mandela was born in a small, impoverished South African village on July 11th, 1918 and was named Rolihlahla Mandela. At nine, Mandela was adopted by and sent to live with his father’s friend, a prosperous clan chief, who could offer him a better life with a proper education. When he learned about African history and how his ancestors struggled with discrimination, the young Mandela developed a goal to somehow help his countrymen. Eventually, Mandela studied law and opened the country’s first Black law practice in Johannesburg. Joining the African National Congress allowed him to fight for racial equality with others who shared his distress.

Mandela Against Apartheid

In response to the government’s introduction of apartheid in 1948, Mandela traveled throughout South Africa imploring people to participate in non-violent demonstrations. Mandela was eventually sentenced to life in prison for organizing these activities and during his trial, passionately stated, “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if need be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.” He was imprisoned as a political prisoner for 27 years, 18 of which he spent on the isolated Robben Island.

First Black President

An epic day in human rights history was February 11th, 1990, when Mandela was released from prison by South African president F.W. de Klerk. The two then went on to work diligently toward successfully abolishing apartheid. For their tireless efforts, Mandela and de Klerk won the Nobel Peace Prize three years later.

In 1994, South Africans participated in their very first democratic election where non-Whites had the opportunity to vote for Nelson Mandela. During his presidency, housing, education, and the economy were improved for his country’s large Black population (though there is still a long way to go). In 1999, Mandela resigned and went on to create The Nelson Mandela’s Children Fund charity. Their mission is to help poor South African children, as Mandela believed that, “Children are the wealth of our country.”

Mandela’s Legacy

Mandela was appointed to the Order of Canada in September 1998 and was the first living person to be named an honorary Canadian citizen.

Mandela founded The Elders in 2007, an organization comprised of world leaders who are dedicated to promoting human rights and global peace. In 2009, July 18th (Mandela’s birthday) was declared “Mandela Day” to honour his legacy and promote global peace.

On December 5th, 2013, Nelson Mandela died peacefully at his home in Johannesburg.

A line written by Poet Saint Thiruvalluvar, who lived 2200 years ago, describes the personal mantra of Mandela: “For those who do ill to you, the best punishment is to return good to them.”

Read more about Mandela’s life and watch the video: Biography of Nelson Mandela

ACTION 2

Peaceful demonstrations versus oppressive violence

The Soweto Uprising: on June 16, 1976, police met thousands of students with violence as the students were marching peacefully to protest the new government mandate requiring the Afrikaans language to be main language of instruction in schools. The uprising spread from Soweto to towns across South Africa over the following year.

While the government’s official death toll of 176 dead in the Soweto Youth Uprising, further estimates put the casualties from the resulting aftermath as high as 700. The images of police brutality against peacefully demonstrating students spark further international outrage.

Do

Listen to “Soweto Blues” the protest song written and recorded in 1976 by Hugh Masakela that refers to the students’ protests. Read the lyrics (translated from Xhosa). Performed by Masakela’s ex-wife, Miriam Makeba: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dMSwlBGcSRs

Do

In groups, create a timeline merging both of the timelines listed above together. Link each action with its opposing action. Label actions (on both sides) as either violent or non-violent. Attach 10 images, or draw pictures (from images you research), to show what the events looked like.

Discuss

Do you think that peaceful demonstrations alone could have changed the fate of apartheid?

What was most effective in putting an end to apartheid?

Considering how violent the South African government was towards the Black population, do you believe that fighting violence with violence would have proved effective in ending apartheid sooner?

Nelson Mandela never hated his oppressors. How do you think he maintained such a peaceful outlook when wrongfully imprisoned for 27 years?

ACTION 3

Do

A. Choose ten pivotal actions from the timeline you have created.

B. Choose one writing assignment from the two below:

- Develop a thesis that reflects on whether violence or peaceful protests work when fighting injustice. Write a persuasive essay about the use of non-violence or violence in putting an end to apartheid. Do not forget to provide evidence from your timeline to demonstrate the authenticity of your thesis.

- Write an essay comparing Nelson Mandela to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and specifically, their particular styles of non-violent protest. Do you believe that one of these leaders was more successful than the other? Defend your viewpoint.

Further Research

Visit the website of the Apartheid Museum in South Africa for additional resources and information.

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming

Educator Tools